Nullcon #HackIM CTF 2026 Writeup

Another year, another Nullcon Goa #HackIM CTF! This time, I spent some time on a challenge called Pasty. It’s a classic example of why “rolling your own crypto” is almost always a bad idea, but a great source of fun for CTF players.

Challenge: Pasty

Category: Web / Crypto

Points: Unknown

Flag: ENO{cr3at1v3_cr7pt0_c0nstruct5_cr4sh_c4rd5}

Challenge Description

The challenge presented a “secure” pastebin service called Pasty. The authors claimed to protect access using custom cryptographic signatures instead of standard libraries.

“Check out our new secure pastebin service! We rolled our own cryptographic signatures to protect paste access - after all, why trust those boring standard libraries when you can build something custom? Can you prove that our homebrewed crypto isn’t as secure as we think and get access to the ‘flag’ paste?”

The main page looked like a standard pastebin where you can create and view pastes.

Public pastes are accessed via URLs like:

http://52.59.124.14:5005/view.php?id=<16-hex-id>&sig=<64-hex-sig>

A sample was provided:

http://52.59.124.14:5005/view.php?id=8043004b3324f157&sig=c0deb42952b51006c1a499dabc488e100ecf17cf825aa125ae7b86863f04834c

Crucially, the signature generation code was shared:

function _x($a,$b){$r='';for($i=0;$i<strlen($a);$i++)$r.=chr(ord($a[$i])^ord($b[$i]));return $r;}

function compute_sig($d,$k){

$h=hash('sha256',$d,1); // raw binary SHA256($d)

$m=substr(hash('sha256',$k,1),0,24); // first 24 bytes of raw SHA256(secret)

$o='';

for($i=0;$i<4;$i++){

$s=$i<<3;

$b=substr($h,$s,8);

$p=(ord($h[$s])%3)<<3;

$c=substr($m,$p,8);

$o.=($i?_x(_x($b,$c),substr($o,$s-8,8)):_x($b,$c));

}

return $o;

}

Vulnerability Analysis

The signature scheme is a custom block-chaining construction over SHA256 blocks with key material derived from a secret. Let’s break it down:

- Compute

h = SHA256(d): This gives 32 raw bytes of the data being signed (the paste ID). - Derive

m = SHA256(secret)[:24]: This results in three fixed 8-byte subkeys:k0 || k1 || k2. - Split

hinto four 8-byte blocks:h0 || h1 || h2 || h3. - For each block

i:sel = h_i[0] % 3-> This chooses one of the subkeysk_sel.temp = h_i XOR k_sel- Output block:

out_0 = temp_0, andout_i = temp_i XOR out_{i-1}(this is the chaining part).

- Signature =

out_0 || out_1 || out_2 || out_3.

The Fatal Flaw

Look closely at the first output block: out_0 = h_0 XOR k_sel.

Since we know the paste ID, we can compute h = SHA256(ID). This means we know h0. We also have the signature, so we know out_0.

The subkey is simply: k_sel = out_0 XOR h_0.

Because sel = h_0[0] % 3 is essentially random, each valid signature we collect leaks one of the three subkeys. By collecting enough signed pastes, we can recover all three subkeys (k0, k1, k2) and then forge signatures for any ID we want!

One more thing: The signed data d is the raw ID string (e.g., “804300…”) encoded as UTF-8, not the binary value. This is important because it means we can sign non-hex IDs like the string "flag".

Exploitation Steps

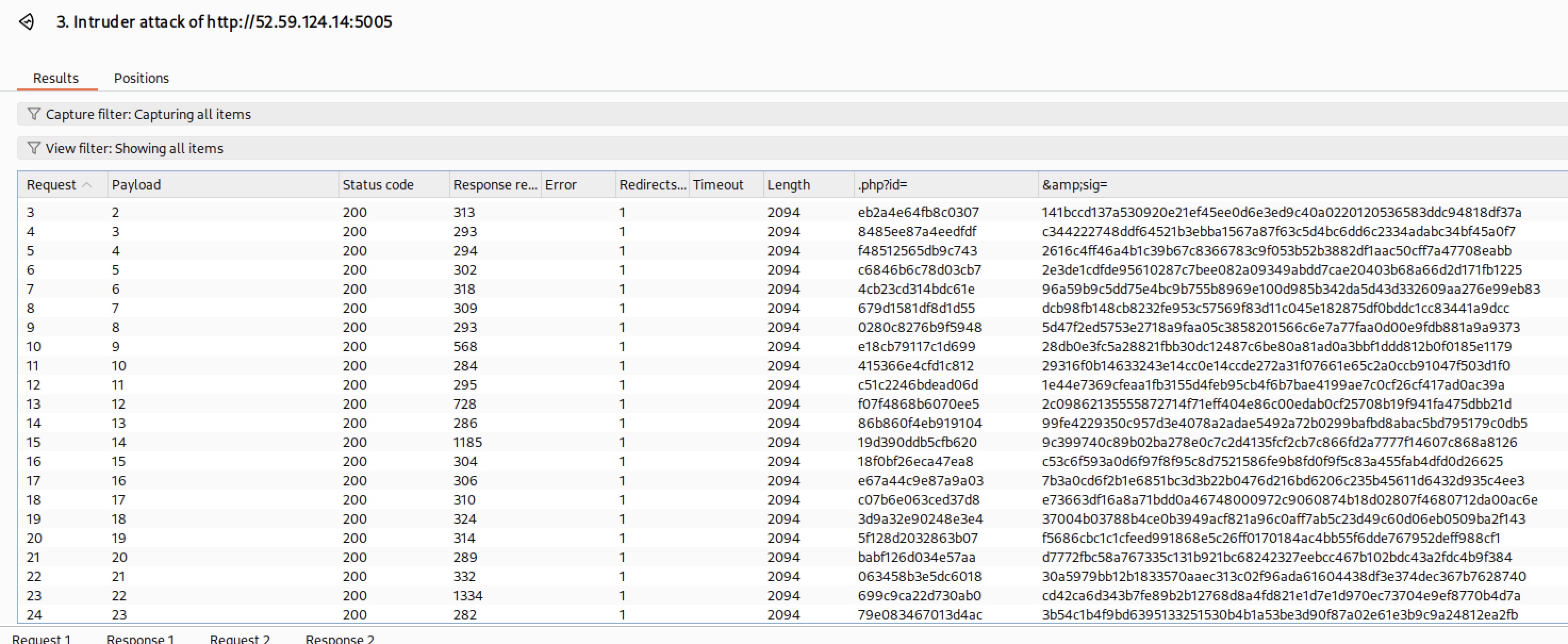

Step 1: Collect Signed Pastes

I used Burp Suite Intruder to create a few dozen public pastes. Each response gave me a valid id and sig pair.

Step 2: Recover Subkeys

With about 20-50 pairs, I took help of a LLM to write a script to extract the keys. For each pair, I computed h0, identified which subkey was used (sel), and calculated the candidate key.

The result confirmed the theory:

- sel 0:

8d77a517320e2c92 - sel 1:

cc04cb3a896051c0 - sel 2:

3899ea82fc144d8a

Step 3: Forge Signature for “flag”

The flag paste likely uses a simple ID like "flag". Using the recovered keys, I implemented the signature logic in Python.

import hashlib

def xor(a, b):

return bytes(x ^ y for x, y in zip(a, b))

recovered_keys = {

0: bytes.fromhex('8d77a517320e2c92'),

1: bytes.fromhex('cc04cb3a896051c0'),

2: bytes.fromhex('3899ea82fc144d8a')

}

def forge_signature(target_id_str):

d = target_id_str.encode('utf-8')

h = hashlib.sha256(d).digest()

# Reconstructing m from recovered subkeys

m = recovered_keys[0] + recovered_keys[1] + recovered_keys[2]

output = b''

prev = b'\x00' * 8

for i in range(4):

start = i * 8

h_block = h[start:start+8]

sel = h[start] % 3

subkey = m[sel*8:sel*8+8]

temp = xor(h_block, subkey)

out_block = temp if i == 0 else xor(temp, prev)

output += out_block

prev = out_block

return output.hex()

# Forge for the flag paste

flag_sig = forge_signature("flag")

print(f"Forged Signature: {flag_sig}")

Result

Navigating to:

http://52.59.124.14:5005/view.php?id=flag&sig=c561b66838a192f153289047918a28f73167be9269cc1225ae7b86863f04834c

(Note: forged sig value depends on the keys)

…revealed the flag!

Flag: ENO{cr3at1v3_cr7pt0_c0nstruct5_cr4sh_c4rd5}

The AI Shift in CTFs & our lives in general.

Recently, there has been a spike in autonomous AI agents playing CTFs and solving challenges in a few minutes. Interestingly, the winner of this year’s HackIM also appears to be such an agent.

CTFs are generally meant for practicing and learning new critical thinking skills. They force you to think and improve your problem-solving capabilities. However, nowadays it has become an AI race where the measure of success relies on two things: Who has the better model? and Who can write better prompts?

AI is here and helping us in many ways, but is it making us dumber? Think about it. Can you start thinking about any problem without asking an LLM these days?

Check this awesome TED Talk for some more insights.

I along with my colleagues solved many other challenges during the CTF under the team name d4rk_cd3c and secured 59th rank overall among 637 teams. It was a fun CTF overall.

Thanks for reading, Happy Hacking !!!

Leave a comment